What is PALS?

Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) is a systematic approach to pediatric emergencies. Its primary focus is on early recognition and to respond to pediatric medical emergencies, including respiratory distress, shock, and cardiac arrest. It is primarily recommended for physicians, nurses, paramedics, and other medical professionals who care for infants and children in emergency settings.

This PALS study guide is most effective for healthcare professionals who already have a solid understanding of pediatric assessment, basic life support (BLS), and rhythm interpretation. Hands-on practice is strongly encouraged before attending a PALS course. Given the depth of information covered in a short time, we recommend reviewing a pre-study guide to reinforce key concepts before taking a PALS certification or renewal course.

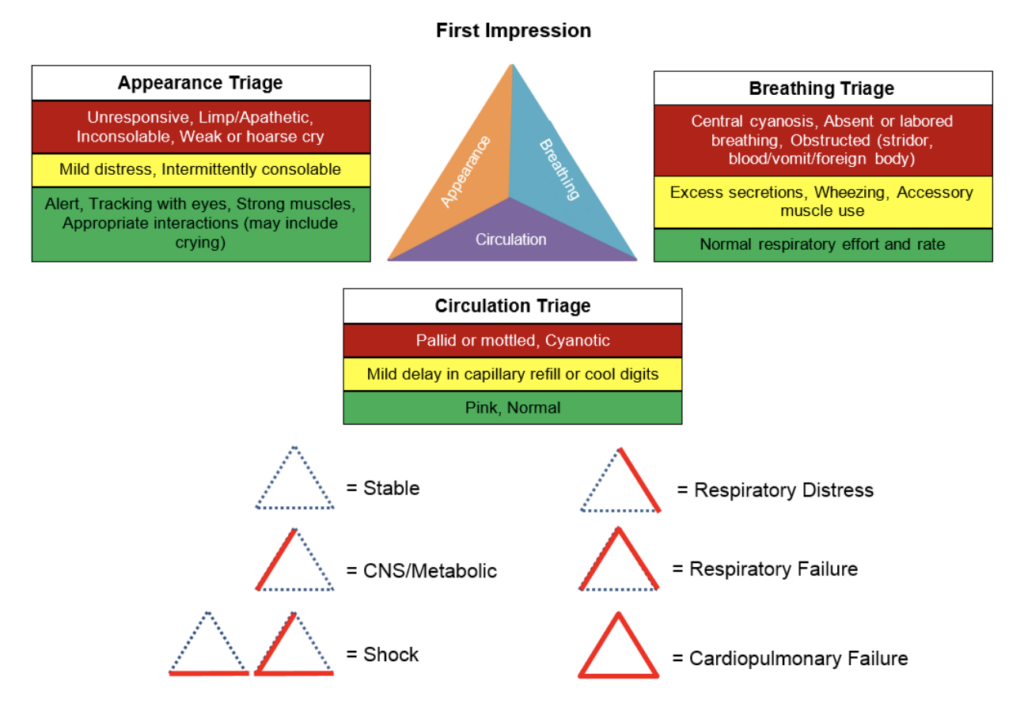

Initial Assessment: Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT)

The Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) is a rapid assessment tool used by healthcare providers to form an initial impression of a child’s clinical status within seconds. It helps determine the severity of illness or injury and guides immediate management decisions without requiring any equipment.

The PAT consists of three components:

1. Appearance (TICLS):

- Tone: Assess muscle tone and movement.

- Interactivity: Evaluate the child’s responsiveness to the environment and interactions with caregivers.

- Consolability: Observe if the child can be comforted.

- Look/Gaze: Note eye contact and attentiveness.

- Speech/Cry: Listen for normal speech or crying patterns

Key Insight: Changes in appearance may indicate neurological or metabolic issues.

2. Work of Breathing:

- Observe for abnormal breathing sounds (e.g., stridor, wheezing).

- Look for signs of increased effort, such as nasal flaring, retractions, or head bobbing.

- Note abnormal positioning like tripod posture or refusal to lie down.

Key Insight: Altered work of breathing suggests respiratory distress or failure.

3. Circulation:

- Assess skin color (e.g., pale, mottled, cyanotic).

- Look for signs of poor perfusion like delayed capillary refill.

- Observe temperature and moisture of the skin.

Key Insight: Abnormal circulation may indicate shock or circulatory compromise.

By evaluating these three components, the PAT helps providers quickly identify life-threatening conditions and prioritize interventions, setting the stage for a more detailed secondary assessment.

Primary Assessment: ABCDE Approach

The Primary Assessment in PALS is a systematic approach to evaluating a pediatric patient’s condition after forming the initial impression using the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT). It follows the ABCDE format to identify and address life-threatening conditions:

A – Airway

- Assess for airway patency (open and maintainable vs. obstructed).

- Look for signs of obstruction (e.g., stridor, drooling, inability to speak or cry).

- Intervene with positioning, suctioning, or advanced airway management if needed.

B – Breathing

- Evaluate respiratory rate, effort, and adequacy (chest rise, breath sounds, accessory muscle use).

- Identify abnormal breathing patterns (e.g., grunting, nasal flaring, retractions).

- Provide oxygen or ventilation support as needed (e.g., bag-mask ventilation, intubation).

C – Circulation

- Assess heart rate, blood pressure, and pulses (central vs. peripheral).

- Check for skin signs (color, temperature, capillary refill time).

- Identify signs of shock (e.g., weak pulses, hypotension, altered mental status) and intervene with IV/IO access and fluid resuscitation.

D – Disability (Neurologic Status)

- Evaluate mental status using AVPU (Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive).

- Assess pupil response and muscle tone.

- Identify signs of increased intracranial pressure or neurologic compromise.

E – Exposure

- Expose the patient as needed to assess for trauma, rashes, burns, or other underlying conditions.

- Maintain normothermia and prevent heat loss, especially in infants and young children.

The Primary Assessment helps identify immediate life-threatening conditions and guides the need for further interventions. It is followed by a Secondary Assessment for a more detailed evaluation, including history and diagnostic testing.

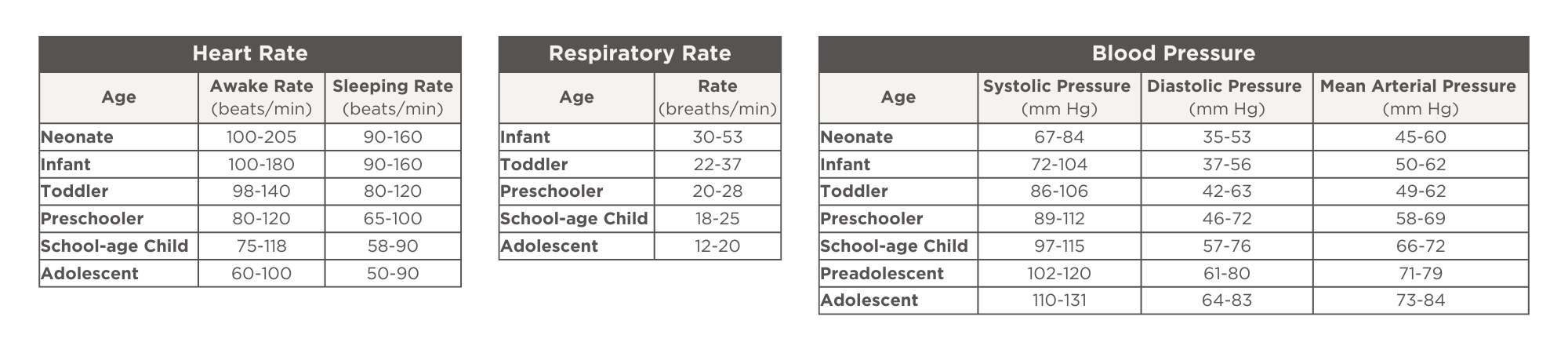

Pediatric Vital Signs Overview

Secondary Assessment: SAMPLE & Focused Physical Exam

The Secondary Assessment in PALS is a more detailed evaluation performed after the Primary Assessment (ABCDE) has identified and addressed any immediate life-threatening conditions. It consists of two main components:

1. Focused History (SAMPLE)

A structured approach to gathering patient history using the SAMPLE mnemonic:

- S – Signs & Symptoms: What is the child experiencing? (e.g., difficulty breathing, altered mental status)

- A – Allergies: Any known allergies to medications, foods, or environmental triggers?

- M – Medications: Any prescription or over-the-counter medications the child is taking?

- P – Past Medical History: Any chronic illnesses, recent hospitalizations, surgeries, or birth history (for infants)?

- L – Last Meal/Oral Intake: When and what was the last food or fluid intake? (important for airway management or potential surgery)

- E – Events Leading to Illness/Injury: What happened before symptoms started? (e.g., trauma, choking, fever, seizure)

2. Focused Physical Exam

A more detailed, head-to-toe examination based on the child’s condition and findings from the Primary Assessment. Key areas of focus include:

- Head & Neck: Look for trauma, swelling, or signs of infection.

- Chest: Assess breath sounds, symmetry, retractions, or abnormal heart sounds.

- Abdomen: Check for distension, tenderness, or rigidity.

- Extremities: Assess for signs of poor perfusion (capillary refill, temperature, pulses) or neurological deficits.

- Skin: Look for rashes, petechiae, cyanosis, or signs of dehydration.

3. Diagnostic Tests & Monitoring

Based on findings, additional tests and monitoring may be necessary:

- ECG for arrhythmias

- Pulse oximetry & capnography for oxygenation and ventilation status

- Blood tests (glucose, electrolytes, blood gases, lactate)

- Imaging (X-ray, ultrasound, CT scan) if needed

The Secondary Assessment helps refine the diagnosis, guide treatment decisions, and monitor the effectiveness of interventions. It follows the Primary Assessment and ongoing reassessment to ensure the child’s condition is improving or to adjust care if necessary.

Respiratory Emergencies

Respiratory emergencies are a leading cause of pediatric cardiac arrest. PALS categorizes them into respiratory distress (increased work of breathing but adequate gas exchange) and respiratory failure (inadequate oxygenation or ventilation).

Category | Causes | Signs/Symptoms | Management |

Upper Airway Obstruction |

|

|

|

Lower Airway Obstruction |

|

|

|

Lung Tissue Disease |

|

|

|

Disordered Control of Breathing |

|

|

|

Key Interventions:

- Oxygen therapy (nasal cannula, non-rebreather, high-flow)

- Bag-mask ventilation (BMV) for inadequate breathing

- Endotracheal intubation for respiratory failure

- Continuous monitoring (pulse oximetry, capnography, blood gases)

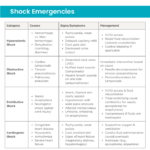

Shock Emergencies

Shock is a critical condition where oxygen delivery to tissues is inadequate, leading to organ dysfunction and failure. PALS categorizes shock into four types, each with distinct causes, signs, and management strategies.

Category | Causes | Signs/Symptoms | Management |

Hypovolemic Shock |

|

|

|

Obstructive Shock |

|

| Immediate intervention based on cause:

|

Distributive Shock |

|

|

|

Cardiogenic Shock |

|

|

|

Key Interventions in Shock Management

- Early recognition using vital signs & perfusion assessment

- Rapid vascular access (IV/IO) for fluid and medication administration

- Fluid resuscitation (except in cardiogenic shock, where fluids are given cautiously)

- Use of vasopressors and inotropes if fluids are not sufficient

- Definitive treatment based on the type of shock

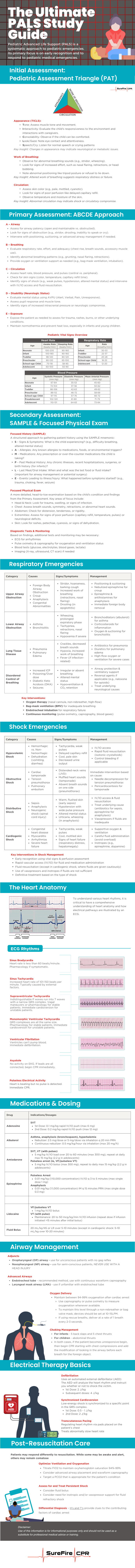

The Heart Anatomy

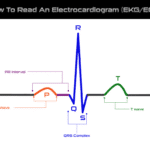

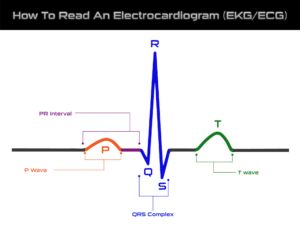

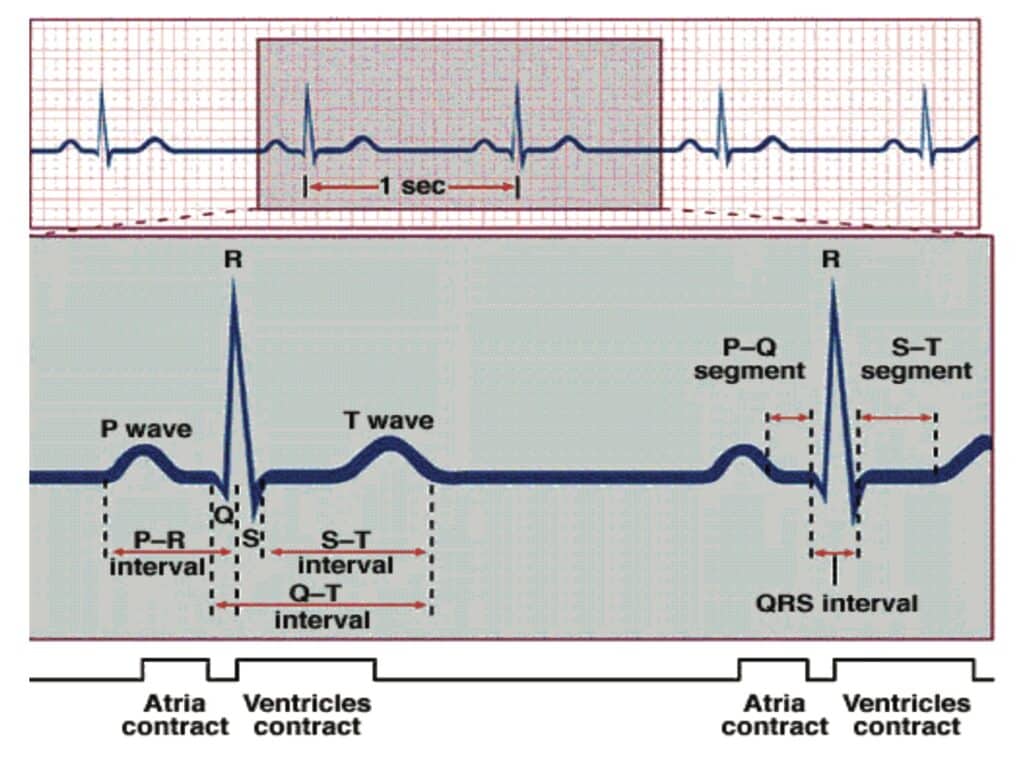

To understand various heart rhythms, it is critical to have a comprehensive understanding of heart anatomy and how electrical pathways are illustrated by an ECG.

Blood enters the heart through the atria, which sends out an electrical impulse through the sinoatrial (SA) node. The impulse travels through the atria, causing contractions that appear as P waves on an ECG.

The impulse travels from the SA node to the atrioventricular (AV) node next. The AV node sends out another electrical impulse that travels through the branches and fibers of the ventricles. Contractions caused by this impulse appear on the ECG and the QRS complex.

When the ventricles rest and repolarize, this activity registers on the ECG as a T wave. The atria also experiences a rest period, but this activity cannot be seen on an ECG.

ECG Rhythms

During your PALS study, you may encounter a variety of heart rhythms, including:

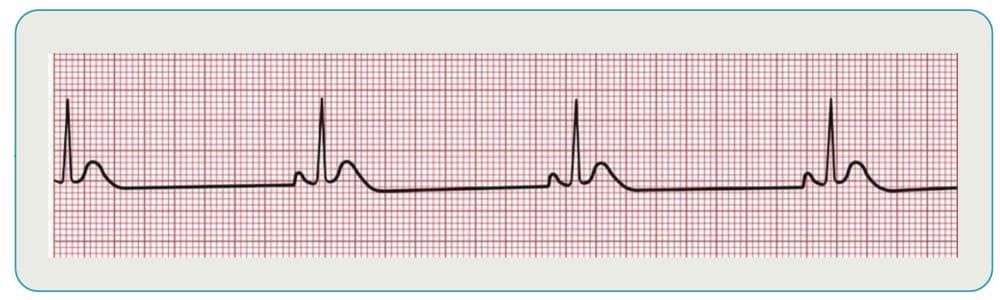

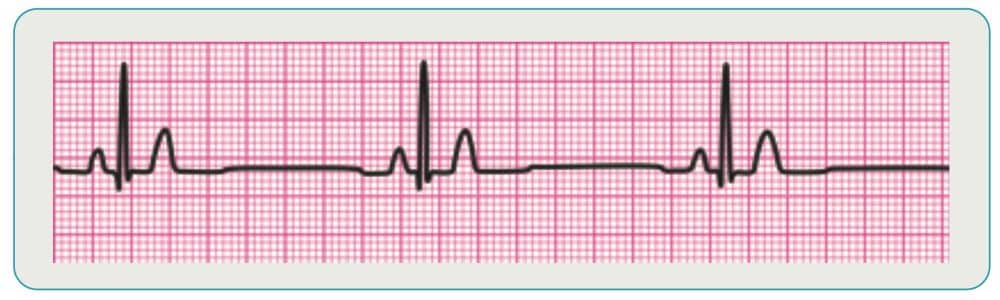

Sinus Bradycardia

This rhythm occurs when the SA node fires at a slower rate appropriate for the patient’s age. Hypoxia is the most likely cause for bradycardia in pediatric patients and should be treated with oxygen using a bag-valve mask (BVM). If the heart rate is less than 60 BPM after rescue breathing, then begin CPR starting with chest compressions.

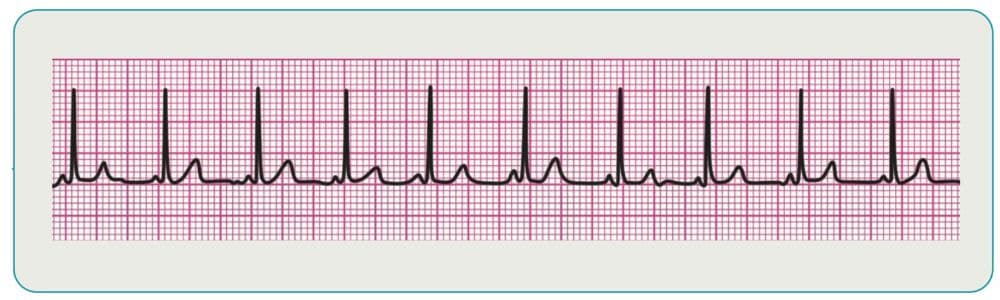

Supraventricular Tachycardia

This category of rhythms is characterized by indistinguishable P waves due to a faster rate. The rhythms also tend to have P waves that run into preceding T waves and narrow QRS complexes. Treatment of stable patients is typically vagal maneuvers or pharmacology, while unstable patients are usually candidates for cardioversion.

Rapid, regular heart rate (>220 bpm in infants, >180 bpm in children).

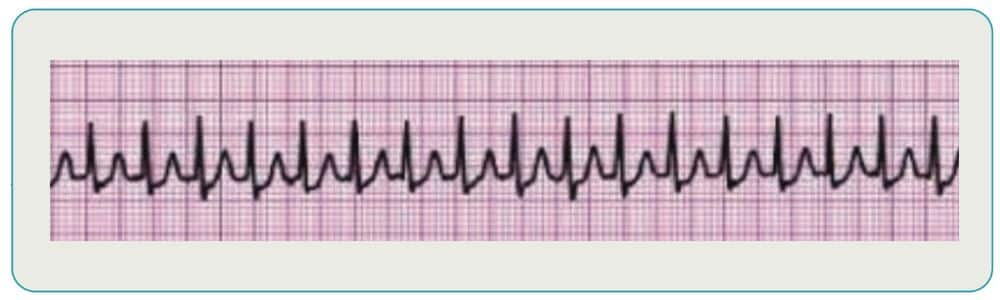

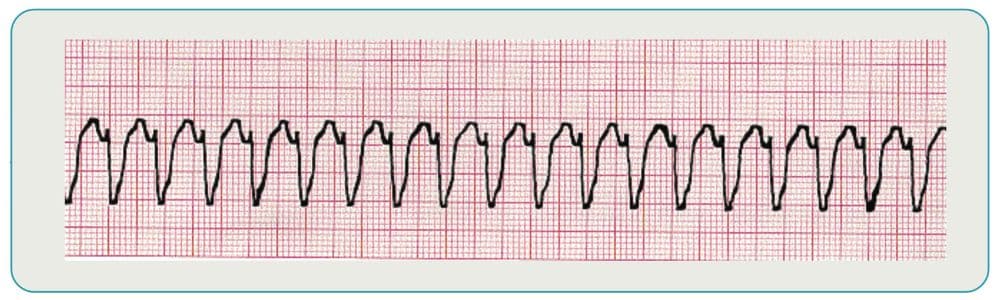

Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

This rhythm occurs when the ventricle takes over control of the heart, increasing its firing rate. It features QRS complexes that are all the same size and shape.

If the patient has a pulse, then it should be treated with pharmacology after an expert consultation and unstable patients should receive immediate cardioversion.

If the patient is pulseless, then it should be treated like ventricular fibrillation.

Medications & Dosing

Drug | Indications/Dosages |

Adenosine | SVT

|

Albuterol | Asthma, anaphylaxis (bronchospasm), hyperkalemia

|

Amiodarone | SVT, VT (with pulses)

Pulseless arrest (ie, VF/pulseless VT)

|

Epinephrine | Pulseless Arrest

Anaphylaxis

|

Lidocaine | VF/pulseless VT

VT (with pulse)

|

Fluid Bolus | 20 mL/kg NS or LR over 5-10 minutes (except in cardiogenic shock: 5-10 mL/kg over 10-20 minutes) |

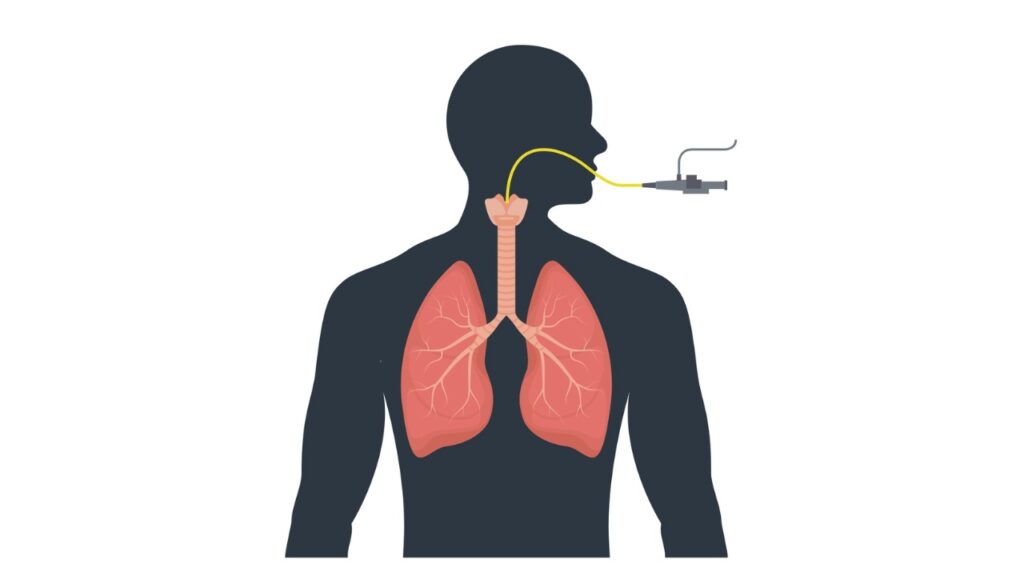

Airway Management

Airway management is another essential element of PALS study and may be performed using adjuncts or advanced airways:

Adjuncts

These devices, which include oropharyngeal (OP) and nasopharyngeal (NP) airways, are used to access and maintain a patient’s airway. NP airways can be used for semi-conscious patients, while OP are recommended for unconscious patients with no gag reflex. Never use an NP on a patient with a head injury.

Advanced Airways

The endotracheal tube is one advanced airway that is recommended for most patients when possible. It is best to use continuous waveform capnography to monitor the placement of the endotracheal tube. Sizing: (Age/4) + 4 for uncuffed, (Age/4) + 3.5 for cuffed tube.

Once the advanced airway is in place, you should continue 100-120 compressions per minute without stopping for breaths. Victims should get 1 breath every 2-3 seconds.

Oxygen Delivery

Oxygenation after cardiac arrest should be maintained between 94-99%, with capnography or pulse oximetry used to measure oxygenation whenever available. To maintain this level through a non-rebreather or bag valve mask, devices should be set at 10-15LPM. If using rescue breaths, they should be delivered at a rate of 1 breath every 2-3 seconds.

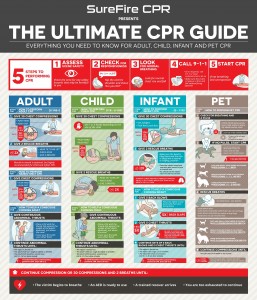

Choking Management

A choking incident can lead to reduced oxygen into the lungs and cardiac arrest if it is not treated quickly.

- For infants: 5 back slaps and 5 chest thrusts

- For children: abdominal thrusts

In both cases, if the patient becomes unresponsive begin, then begin CPR starting with chest compressions and add the modification of looking in the airway before each breath for the foreign object.

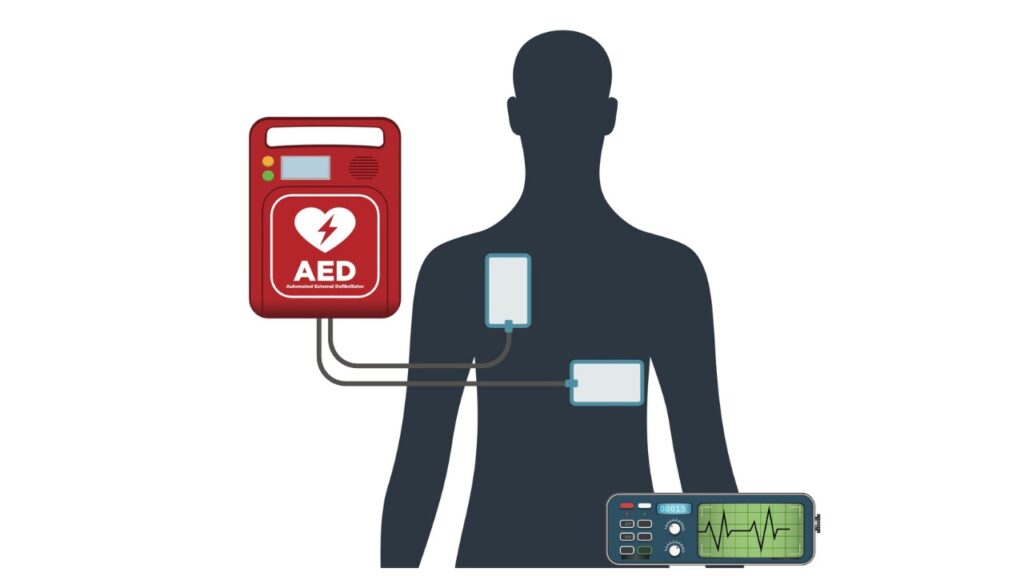

Electrical Therapy Basics

There are three ways to administer electrical therapy as part of your PALS study guide:

Defibrillation

An automated external defibrillator (AED) is a device that restores normal heart rhythm using a controlled electrical shock. To operate an AED, turn the device on and place the pads on the victim’s chest. If the child is big enough, then 1 on the upper right side and 1 on the lower left side. If the patient is an infant, then 1 on the front (center of the chest) and 1 on the back (between the shoulder blades). The AED will analyze the heart rhythm and instruct you whether or not to shock the victim.

- 1st Dose: 2 J/kg

- Subsequent doses: 4 J/kg

Synchronized Cardioversion

Synchronized cardioversion is similar to defibrillation, but delivery of the low-energy shock is synchronized to a specific point in the QRS complex. The timing is designed to prevent ventricular fibrillation as a result of the shock.

- 1st Dose: 0.5 – 1 J/kg

- 2nd Dose: 2 J/kg

Transcutaneous Pacing

This treatment, which involves regulating heart rhythm via pads placed on the patient’s chest, can be used to address an abnormally slow heart rate.

Post-Resuscitation Care

Patients may respond differently to resuscitation. While some may be awake and alert, others may remain comatose.

Optimize Ventilation and Oxygenation

- Titrate FIO2 to maintain oxyhemoglobin saturation 94%-99%

- Consider advanced airway placement and waveform capnography

- Target a PCO2 that is appropriate for the patient’s condition

Assess for and Treat Persistent Shock

- Consider fluid bolus

- Consider need for inotropic and/or vasopressor support for fluid refractory shock

Differential Diagnosis – H’s and T’s provide clues to the contributing factors of cardiac arrest

Case Scenarios

PALS case scenarios are essential for simulating real-life pediatric emergencies, helping healthcare providers apply theoretical knowledge in a practical, hands-on way. These scenarios enhance critical thinking, teamwork, and communication by requiring participants to make fast decisions in high-pressure situations, while practicing vital interventions such as CPR, airway management, and defibrillation. They also improve recognition and management of various pediatric conditions like respiratory distress, cardiac arrest, and shock. Through these realistic simulations, providers can build confidence, refine skills, and learn from debriefing sessions, all of which prepare them for handling actual pediatric emergencies effectively and efficiently.

Case Scenarios

PALS case scenarios are essential for simulating real-life pediatric emergencies, helping healthcare providers apply theoretical knowledge in a practical, hands-on way. These scenarios enhance critical thinking, teamwork, and communication by requiring participants to make fast decisions in high-pressure situations, while practicing vital interventions such as CPR, airway management, and defibrillation. They also improve recognition and management of various pediatric conditions like respiratory distress, cardiac arrest, and shock. Through these realistic simulations, providers can build confidence, refine skills, and learn from debriefing sessions, all of which prepare them for handling actual pediatric emergencies effectively and efficiently.

PALS Certification Prepares You for Life-Threatening Pediatric Emergencies

Are you ready to get PALS certified? This course prepares healthcare providers for life-threatening pediatric emergencies by offering structured, scenario-based training that simulates real-world situations. It teaches you how to quickly recognize and assess critical conditions, such as respiratory distress, shock, cardiac arrest, and trauma, and how to apply appropriate interventions in high-pressure environments. The team at SureFire CPR offers traditional in-person and hybrid only PALS certification courses. The hybrid model combines online training modules, followed by a brief in-person skills check at any of our locations. We also offer recertification courses for healthcare professionals looking for PALS renewal.

FAQ’s

What is the purpose of a PALS study guide?

The PALS study guide provides step-by-step instructions on how to respond to pediatric emergencies. While the PALS course teaches all the skills necessary to treat patients in these emergencies, the PALS study guide offers information reminders you might need in the event of an emergency. It should be kept with you while your certification is current for easy reference.

What is PALS, and who needs it?

PALS is a certification program designed to teach healthcare providers how to respond to pediatric emergencies, including respiratory and cardiac arrest, shock, and other critical conditions in children. It is typically required for doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals who work in emergency or pediatric settings.

What does the PALS certification include?

The PALS course includes a mix of lectures, hands-on practice, and case scenarios. You’ll learn how to manage pediatric emergencies, including:

- Advanced airway management (e.g., intubation)

- CPR for children and infants

- Medication dosages and administration in pediatric patients

- Recognition and treatment of shock, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest

What if I'm not a pediatric specialist—will PALS still be useful for me?

Yes! PALS is designed for all healthcare professionals, not just pediatric specialists. Whether you work in adult care, emergency medicine, or ICU, understanding pediatric emergencies is critical, as you may encounter children in urgent care or hospital settings.

How is PALS different from ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support)?

While both PALS and ACLS teach advanced life support techniques, PALS is specifically tailored to pediatric patients, whereas ACLS focuses on adult patients. PALS covers age-specific CPR and emergency protocols for infants, children, and adolescents, while ACLS focuses on adult cardiac arrest management.